Between bone-lines

and water’s map,

what lingers moves unseen –

a script of salt,

unspooled beneath the skin.

The child does not know

the weight they carry,

how old hands pressed

before they curled to form

themselves.

Through blood-thread

and quiet etching,

a mark remains –

not of wounds seen

but of what was given

without touch.

In the marrow’s hush,

a memory takes root

not as story

but as something the body

has always known.

This poem is inspired by recent research, which found war-related trauma changes DNA in Syrian refugee families, affecting children and grandchildren.

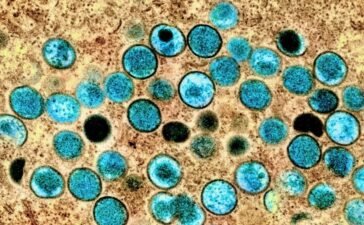

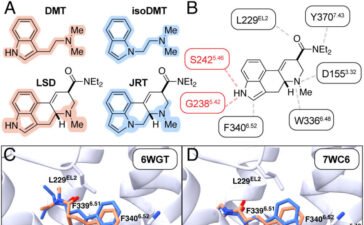

Violence does not just affect those who experience it directly – it can have lasting effects across generations. Trauma during pregnancy may alter how genes function through biological changes known as epigenetic modifications, potentially shaping long-term health. While past research has shown that trauma impacts individuals, less is known about how these effects are passed down. Understanding this process is crucial for recognising the lasting consequences of conflict and displacement, particularly for refugee communities.

This study examined DNA patterns in three generations of Syrian refugees to explore how war-related violence influences gene expression. Analysing biological samples from 131 participants, researchers found clear genetic markers linked to both inherited and direct exposure to violence. Children exposed to trauma before birth showed signs of accelerated ageing, highlighting pregnancy as a critical period of vulnerability. This research offers the first direct evidence of a biological signature of intergenerational trauma, shedding light on how conflict affects families long after it ends.

Discover more from The Poetry of Science

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.