WASHINGTON — First, it was Washington D.C. and New York City. Later, it was Martha’s Vineyard. In the last few weeks, the great immigration debate has reached new levels, as Republican governors from Arizona, Florida and Texas have been shipping asylum seekers to more liberal-leaning Democratic enclaves. Behind their moves has been a simple argument, the people coming over the border are a problem to be dealt with.

But a closer look at the numbers around immigration and the nation’s labor force, particularly since the Covid pandemic, raises questions about that theory of the case.

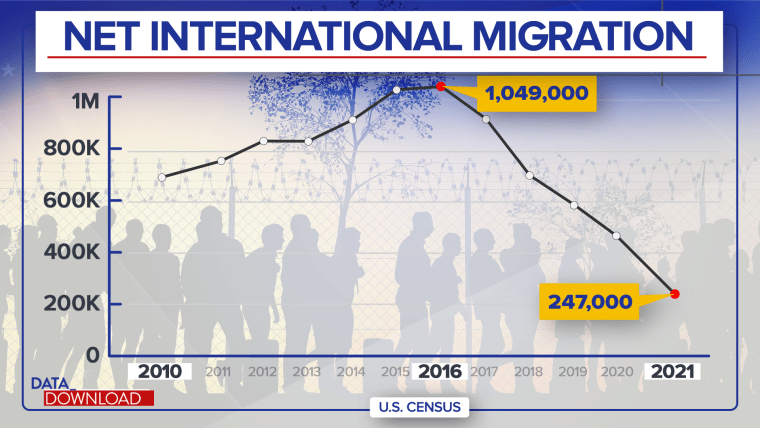

Even before the pandemic, net international migration into the United States had been slowing according to the U.S. Census.

In 2015 and 2016, the United States saw a net international migration gain of more than 1 million people. It dipped to about 930,000 in 2017 and dropped to just over 700,000 in 2018. By 2020, the year of the pandemic’s arrival, it was under 500,000. And last year, the figure dropped to about 247,000.

That’s a massive and sudden decline that, among other things, subtracted a lot of potential workers from the U.S. economy and it was bound to have ripple effects. Some of those impacts were masked by the disruptions of the pandemic, when businesses were shuttered and unemployment rates spiked.

But one of the primary hallmarks of the rebooting U.S. economy has been a worker shortage, a plethora of “help wanted” signs in the windows of retailers, restaurants and other businesses in communities across the country.

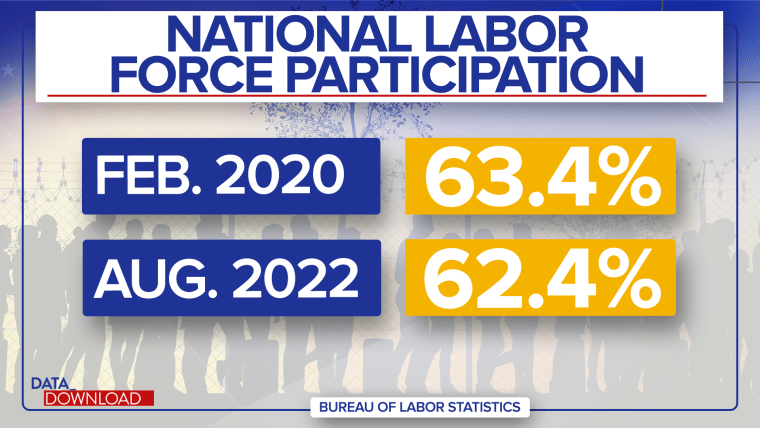

You can see the signs of that shortage in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Labor Force Participation Rate.

That number for August was 62.4% and it was one percentage point lower than where it stood in February of 2020. One percentage point might not sound like a lot, but it equals about 2.6 million fewer people with jobs or actively looking for jobs compared to February 2020.

And that 62.4% number is historically low. The last time the Labor Force Participation Rate hit that number (pre-pandemic) was for one month back in September 2015. Before then, you have to go all the way back to the late 1970s to see a number that low.

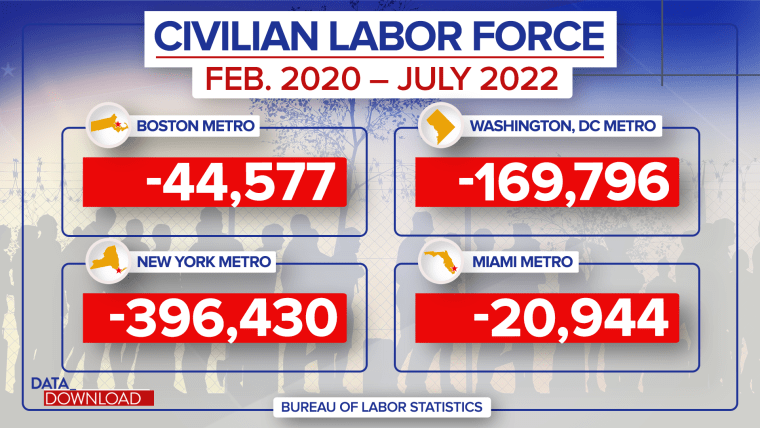

The post-Covid challenges are particularly pronounced in some of the nation’s bigger cities, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In the Boston metro area, the civilian labor force number is still down about 45,000 workers from where it was in February of 2020, in BLS data. In metro Washington D.C., a bigger area, the labor force number is almost 170,000 workers down from where it was in February of 2020. And in the massive New York City metro, the labor force figure is down almost 400,000 from where it was pre-pandemic.

And it’s not all northern cities. Metropolitan Miami is down about 21,000 workers from where it was pre-pandemic.

In Boston, Washington D.C. and Miami, the unemployment rate was at or below the national figure in the latest set of data. At the very least, the numbers suggest those are very tight labor markets that could probably use an infusion of potential workers.

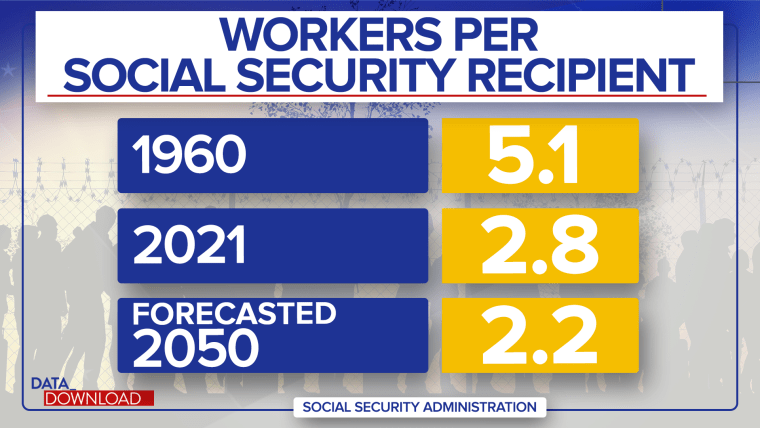

And new workers are crucial to the larger U.S. economy beyond the current labor shortage.

The United States has an aging population, an aging labor force and a declining birthrate. Those factors combine to affect a host of government programs, but the impacts could be the most profound on Social Security, which relies on a steady stream of new workers to keep paying into the system to keep it afloat.

The problem becomes apparent when you look at the ratio of workers per Social Security recipient.

Back in 1960, there were 5.1 workers for every Social Security recipient. That number declined steadily through the 1970s and 1980s and currently sits at 2.8 workers for every recipient, according to the Social Security Administration. Over the 30 years, the number is forecasted to dip to about 2.2 workers for every recipient.

The math isn’t very complicated. At some point longer lifespans and lower birthrates combine to create a massive problem for the program. Without more workers in the economy, the day of reckoning is likely to come sooner.

To be clear, the governors who moved the asylum seekers, Florida’s Ron DeSantis, Arizona’s Doug Ducey and Texas’s Greg Abbott, were trying to make a political point, or pulling a political stunt, depending on your point of view. Bus and plane loads of immigrants were shipped to other locales and without consulting or coordinating with the local governments in their destinations. The goal was to create chaos.

But the larger idea behind all the buses and planes, that the asylum seekers are problematic or a nuisance, may miss a larger truth. The data suggest the United States is sorely in need of workers right now.

And once they get settled in, the immigrants that the governors are shipping to bluer political lands may turn into an asset for those communities and the larger U.S. economy.