‘One, two, three – order is about counting, about serialising, joining together. Order makes clear what’s up and down, what comes earlier and what later. Order helps us understand, predict and control. Order is the structure of something. The opposite of chaos. And chaos, when not experienced as the thrill of transgression, is frightening.’

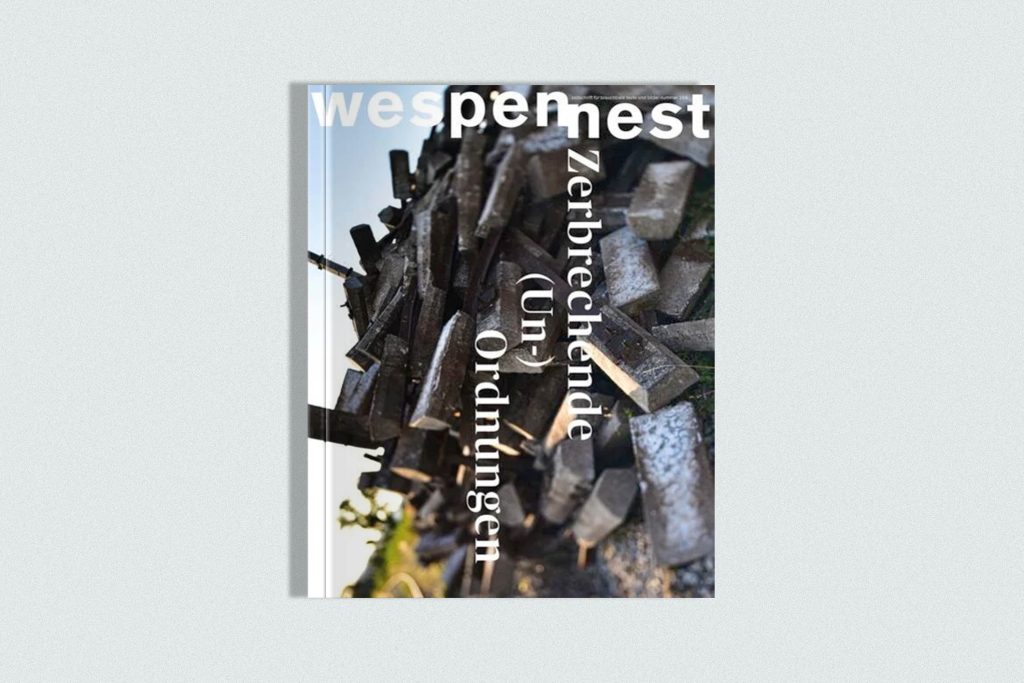

Entitled ‘Collapsing (dis)orders’, the aim of the new issue of Wespennest is – as editor Andrea Roedig puts it – ‘to capture the prevalent feeling of threatening upheaval, the oft-cited Zeitenwende that rather promises an abrupt departure from familiar (dis)orders. The foundations of neoliberal laissez-faire and certainties about the European post-war order both seem to be falling away. Central heating is being regulated (at least in Germany) and tanks are being sent east with minimal pomp.

Crisis of the neoliberal order

‘The world is becoming ever more confusing,’ writes the political scientist Natascha Strobl. ‘Old certainties disappear, new truths are propagated. That’s the essence of crises. And crises demand solutions.’

Authoritarian forces have long since reorganized and formed new strategies. Now the left needs to do the same. ‘Solidarist crisis solutions must be established. They need to be turned into premises to secure a liveable future for eight billion people. That might sound radical, but so too are the authoritarian counter-solutions.’

But even the ‘normal’ functioning of neoliberal governance tends towards authoritarian etatism, writes political scientist Birgit Sauer.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, crisis-Keynesianism threw ‘essential workers’ the crumbs while dividing the pie between the big players of ‘platform capitalism’. The ‘authoritarian revolt’ of the anti-vaxxers was a cry for freedom that ‘had no idea of equality, let alone solidarity. Rather, it stood in the tradition of neoliberal egoism.’ Far from a more equal state, we are now seeing a new phase of global competition: the West against China.

But because crises are never unambiguous, Sauer sees an opportunity. Younger generations have the potential to form a ‘new state compromise’. This would include ‘not just profit-oriented forces’, but also organizations that ‘aim for the sustainability of life, care for human beings and the environment, and justice’. She envisages a ‘new order of social co-existence – beyond the authoritarian state, but still on the terrain of always-contested statehood.’

In defence of etiquette

The rules of political etiquette are being forgotten, laments writer and civil servant Meinhard Rauchensteiner. Take Sofagate. When Charles Michel accepted that chair next to Erdoğan, leaving Ursula von der Leyen no choice but the sofa, there was outrage. ‘Sexism!’, cried the media – and von der Leyen herself.

But as president of the EU Commission, von der Leyen ranks ‘only’ as a head of government. The president of EU Council, on the other hand, is equal to a head of state. Had Michel given up his seat next to the Turkish president, diplomatic protocol would have been breached.

Which raises the question as to why von der Leyen appeared to be insulted. After all, top-level diplomatic meetings are prepared minutely in advance. Was she using the occasion to get one over a competitor?

Intrigue aside, Rauchensteiner’s main concern is with defending ‘ritualized forms of behaviour’. ‘They are perceived as outdated, their meaning is no longer understood, their supra-individual gesture considered not a handhold but as something distant from individual needs. Yet rituals and ceremonies are supposed to be just that: a handhold. As Roland Barthes put it: “ceremony protects us like a house: it makes feelings habitable”.’

Charles Michel claimed the incident had cost him sleepless nights. Had he also understood this principle, he might have slept better.

Also to look out for

Ethnologist Ulrich van Loyen on death cults and the order of southern Italian society – why the mafia believes in bureaucracy; historian Stephan Steiner on the chaos caused by the 11-day gap between the Julian and Gregorian calendars in the 18th century; and historian Valentin Groebner on ageing and the wobbling of the gender order.