For the past four years I have had the privilege to teach a dual enrollment class on American Indian History. While I love teaching this course, it can be difficult to find primary source documents. This year I had the opportunity to use Ashbrook’s Core Documents book, Native Americans, edited by Jace Weaver. This edition provides documents that are concise and include helpful contextual information. One of the documents from this collection that I used this year was Document 42, “United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, Justice Harry Blackmun, Justice William Rehnquist,” June 30, 1980.

Essential to teaching American Indian history is a focus on the language of treaties. These documents form the legal basis of interaction between sovereign American Indian nations and the government of the United States of America. These agreements have been frequently used by Native nations in efforts to obtain the rights and lands codified within and established as law by the Constitution (Article II, Section 2). All too often, the United States government has violated the promises made in those documents.

The Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians, presents students with a case that demonstrates the legitimacy of treaties within the framework of the federal courts. It is a relatively recent decision that reaches back to the history of westward expansion and Native efforts to maintain their sacred spaces. The treaty at the heart of the case is the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. That treaty reflects the strong position the Lakota and their Cheyenne and Arapaho allies were in at the conclusion of Red Cloud’s War. This conflict was notable for U.S. army defeats like the Fetterman Fight, an engagement that left 81 soldiers dead and made a name for a young Oglala warrior named Crazy Horse. The United States was forced to sue for peace, and the resulting treaty created the Great Sioux Reservation that included the sacred Black Hills.

The terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty were generally favorable to the Lakota and their allies. It is important for students to understand the ways in which American Indian nations resisted westward expansion, and how they achieved notable success in Red Cloud’s War. The United States agreed to remove several forts from the Bozeman Trail, and the Great Sioux Reservation was effectively all of modern South Dakota. The inclusion of the Black Hills was critical from the Lakota perspective. The Black Hills were a sacred space and one that they were determined to maintain. Article XII of the treaty states, “No treaty for the cession of any portion or part of the reservation herein described which may be held in common shall be of any validity or force as against the said Indians, unless executed and signed by at least three-fourths of all the adult male Indians, occupying or interested in the same.” This provision offered a safeguard against a minority-brokered alternative deal with the government, as had happened among the Cherokee several decades before. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, negotiated from a position of strength, granted the Lakota lands that would preserve their people for the future.

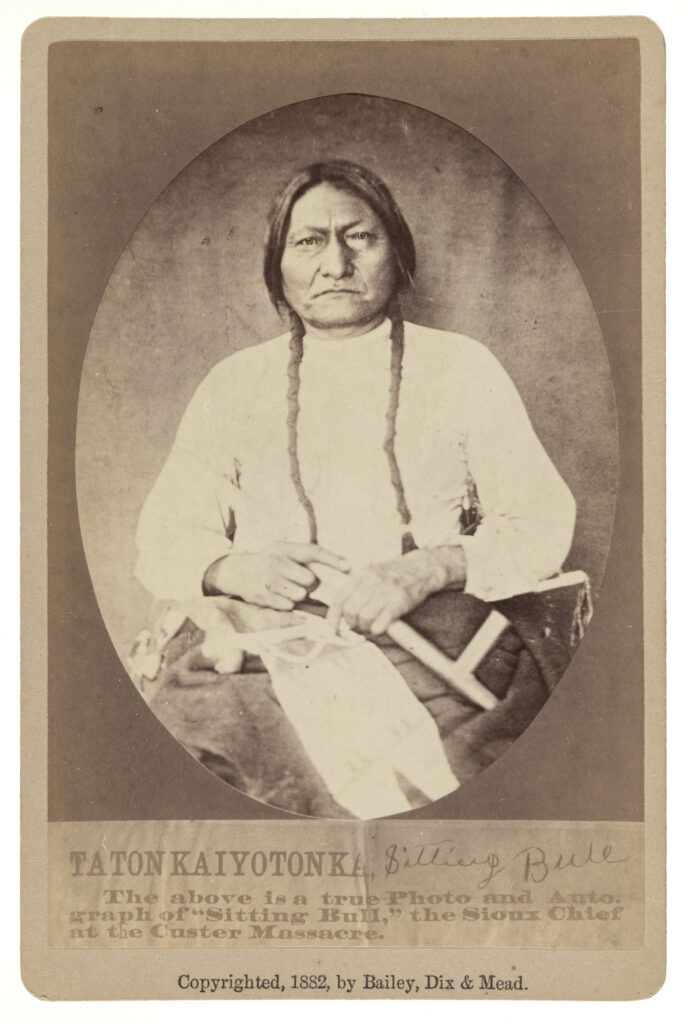

The circumstances had changed by 1877 when a new agreement was codified in law between the Lakota and the United States. General George Custer had led a military expedition into the Black Hills in 1874 and discovered gold. A wave of illegal miners flooded the Great Sioux Reservation prompting the Lakota to defend their land. The Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, where General George Custer met his ignoble end, had hardened American attitudes towards Native bands living off the reservations. The subsequent U.S. military campaigns against the Lakota and Cheyenne greatly reduced Indigenous autonomy, witnessed Sitting Bull’s flight to Canada, and the killing of Crazy Horse at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. This was the context in which the U.S. Congress changed the terms of the previous Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 and took the Black Hills away from the Lakota, greatly reducing the land base of the Great Sioux Reservation. Only ten percent of adult males agreed to these new terms, a violation of the original treaty that required three-fourths of adult males to agree to any changes.

The Lakota never accepted the “forced forfeiture” of the Black Hills, their sacred site, in 1877. They sought redress in Congress and pursued a series of legal actions that eventually led to the Supreme Court decision in 1980.

Judge Blackmun wrote the 8-1 majority decision. Blackmun immediately highlighted that the case was about the Black Hills and the establishment of the Great Sioux Reservation by the terms of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. Blackmun then demonstrated that the law of 1877 had the “effect of abrogating the earlier Fort Laramie Treaty.” Blackmun came to this conclusion based on the language of the original treaty, specifically Article XII that stipulated that three-fourths of all adult Indian males had to agree to any land cession. Blackmun’s writing in this part of the majority is clear and concise. It relies on the treaty language and effectively illustrates the historical grievance of the Lakota Nation.

Blackmun and his colleagues also concluded that the 1877 Act did not effect “a mere change in the form of investment of Indian Tribal property.” Rather, the Act effected a “taking of tribal property” that had been set aside for “exclusive occupation of the Sioux by the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.” The court decided that it was up to the United States government to make just compensation to the Lakota Nation, including compounding interest, for the taking of the Black Hills.

In his dissent, Justice Rehnquist made an argument that Congress in 1978 had overstepped its Constitutional bounds when it passed a law allowing a new trial in the midst of the Lakota Nationa’s legal proceedings against the U. S. government. According to Rehnquist, this was “nothing other than an exercise of judicial power reserved to Art. III courts that may not be performed by the Legislative Branch.” While Rehnquist’s point has merit, he continued that “It seems to me unfair to judge by the light of ‘revisionist’ historians or the mores of another era actions that were taken under pressure of time more than a century ago,” a reference to Congressional actions in 1877. This sentiment is at odds with acknowledging the legitimacy of treaties. Moreover, it shows a lack of empathy for the reality of the situation of the Lakota people in the present. The Black Hills has become a major tourist destination through the construction of Mount Rushmore. The fact that such an edifice is a desecration of a holy site is only part of the point. Reservations like Pine Ridge, Rosebud and Standing Rock, where the Lakota live, are among the poorest places in the United States. To make a claim that “revisionist historians” have somehow misconstrued the language of the Fort Laramie Treaty struck my students as disingenuous and further proof that obtaining treaty rights from the government will be an uphill battle.

The United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians is an important case to study. The Black Hills are a sacred place to the Lakota, yet they have become kitsch Americana with motorcycle rallies and a rock face edifice dedicated to men who facilitated the taking of Native land. By acknowledging the legitimacy of the Fort Laramie Treaty, the Supreme Court in United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians validated the importance of treaties and their place in American Indian studies. The language of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 and the lands of the Great Sioux Reservation continue to matter as the protests around the North Dakota Access Pipeline have shown. Ultimately, the fact that some of the poorest Americans continue to refuse the fiscal compensation for the taking of the Black Hills, now valued at over $2 billion dollars, illustrates the centrality of land and the spiritual power of the Black Hills for the Lakota people.

Reid Benson is a 2018 MAHG Graduate and teacher at Cass Lake-Bena High School in Cass Lake, Minnesota.

Suggestions for further reading:

Blackhawk, Ned, and Means, Jeffrey D. “The dark history of Mount Rushmore.” https://ed.ted.com/lessons/the-dark-history-of-mount-rushmore-ned-blackhawk-and-jeffrey-d-means

Hamalainen, Pekka. Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019. 273-286.

Smithsonian: National Museum of the American Indian, “Northern Plains Treaties: Is a Treaty Intended to be Forever?” https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/plains-treaties/index.cshtml#title

Treuer, David. The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee: Native America From 1890 to the Present. New York, NY: Riverhead Books, 2019. 151-161.